Shipbreaking: A Deadly Industry

- Human Rights Research Center

- Jul 31, 2025

- 6 min read

Author: Mathilde Guenin

July 31, 2025

View the interactive visual report here on Tableau.

![[Image credit: Mike Hettwer via National Geographic Magazine]](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/e28a6b_08ab74ad0c1e4af1bfe2a852333b18f4~mv2.png/v1/fill/w_980,h_510,al_c,q_90,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/e28a6b_08ab74ad0c1e4af1bfe2a852333b18f4~mv2.png)

Shipbreaking, the process of dismantling end-of-life ships to recover usable parts or for disposal, can be more challenging than one thinks. This procedure occurs primarily due to the complexity of the recycling process, due to the size of the ships as well as the environmental, safety, and human health issues to be managed (OSHA, n.d.).

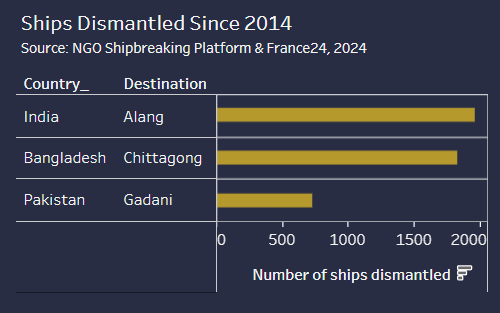

Shipbreaking is mostly located in countries with large coastlines and lower labour costs. Major shipbreaking hubs include Chattogram in Bangladesh, Alang in India, and Gadani in Pakistan.

Due to the complexity and the negative consequences that shipbreaking can have on the environment and workers, there are many regulations put in place by the International Maritime Organization (IMO) and the European Union. The aim of regulating such activities is to ensure that developed countries also take part in the recycling process, rather than sending obsolete vessels to poorer countries to be dismantled. Having developed nations participate can help promote recycling methods that respect human rights and the environment.

1. European Union (EU) Ship Recycling Regulation (SRR), 2018: Ships flying the flag of an EU country must be recycled in an approved ship recycling facility listed by the European Commission. These facilities must meet high standards for worker safety and environmental protection, such as properly handling hazardous materials to prevent environmental pollution (Shipbreaking Platform, EU regulation).

2. Basel Convention, 1992: Prohibits the export of hazardous waste, such as dismantling ships, and aims to prevent their dumping in developing countries by promoting local waste treatment (Shipbreaking Platform, The Law, n.d.).

3. Hong Kong Convention (HKC), 2025: Provides guidance to ensure that ships, when recycled, do not pose risks to human health or the environment (IMO, n.d.).

However, even with these regulations, enforcement is poor, and companies have found ways to bypass the laws.

How Do They Bypass the Law?

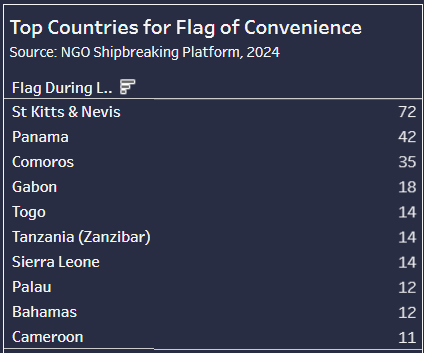

One way companies bypass the law is by using the Flag of Convenience (FOC). It is when a shipowner registers a ship in a different country than their own to avoid strict laws or high taxes (ITF Global, n.d.). These flags are usually from countries like Panama, Comoros, or Saint Kitts and Nevis, as these nations have more lenient rules for exporting end-of-life vessels, which can be sent to countries with poor labor and environmental standards. For example, out of 409 last voyages in 2024, 72 used Saint Kitts and Nevis as the FOC.

For example: A French company owns an old ship that needs to be dismantled. EU laws require that ships be recycled within a certified facility listed by the European Commission; usage of this facility can be more expensive than a nation may want to pay. To bypass these rules, the company changes the ship's flag from France to Panama. Now, on paper, it is a Panamanian ship, and both French and EU laws no longer apply. The company then sends the ship to countries like Bangladesh or India for dismantling, where it is much cheaper, but often unsafe for those involved in the process, in addition to being harmful to the environment.

Poisoned Ground, Forgotten Lives

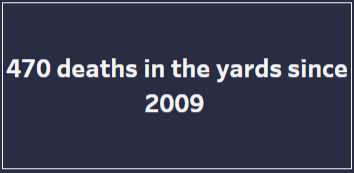

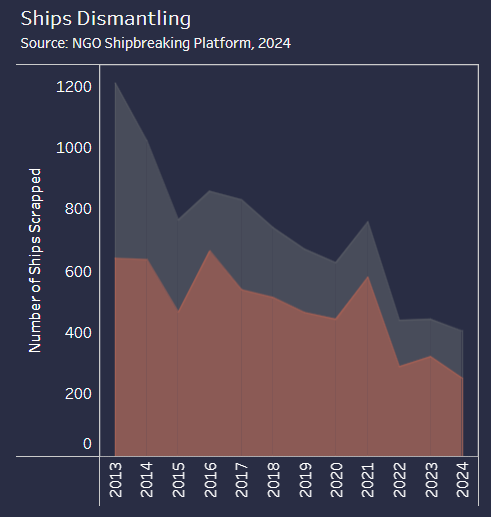

In 2024, out of 409 ships dismantled worldwide, 255 were broken up on beaches, primarily in South Asia. This very dangerous method is known as "beaching." Ships are scrapped directly on or near beaches instead of at specialized shipbreaking yards equipped with proper infrastructure, such as impermeable flooring and wastewater treatment systems. Workers often lack basic protective gear, such as gloves and masks, and adequate training, making them vulnerable to injuries and health issues (Human Rights Watch, 2023). According to the Shipbreaking Platform, since 2009, at least 470 workers have died while working in shipbreaking yards. The common causes are heavy steel beams and plates that can fall and kill workers, as well as explosions and fires (Shipbreaking Platform, The Human Cost).

Moreover, the beaching process is often unregulated and, as mentioned, lacks proper infrastructure, resulting in toxic waste contaminating the environment. Dangerous pollutants such as asbestos, persistent organic pollutants (POPs), heavy metals, and oil residues are released during shipbreaking. These substances, if not managed in a specialized yard, can contaminate ecosystems, endanger marine life, and threaten people’s lives. For instance, in Bangladesh, people who depend on fishing have reported that fish populations have declined in some areas and certain species have disappeared due to the beaching process threatening their access to food (Shipbreaking BD, n.d.).

The shipbreaking industry can be important for countries like India, Bangladesh, and Pakistan, where it provides employment and supports local economies. For instance, in Alang, India, the industry generated an annual revenue of $756 million and employs up to 30,000 people (Peal, 2024). Moreover, in Bangladesh, the industry supplies 80% of the country’s national demand for steel (Anthropology, 2024), and its annual value is estimated at $1.5 billion (IJSSR, 2024).

Conclusion

Shipbreaking plays a significant role in the development of countries and is vital for global recycling. It will continue to exist and is expected to boom in a few years, with the global fleet aging from the 1990s (Port News, 2023). Developed countries should help developing nations to make the industry sustainable and safe through funding, technology sharing, and policy cooperation. Simply imposing bans on the export of end-of-life ships often leads shipowners exploiting loopholes like flags of convenience to avoid compliance. A collaborative and well regulated approach is essential to make shipbreaking safe while ensuring it continues to contribute meaningfully to the development of countries.

Downloadable version below.

Glossary

Asbestos - A highly heat-resistant fibrous silicate mineral that can be woven into fabrics, and is used in brake linings and in fire-resistant and insulating materials (Source : Oxford).

Basel Convention - https://www.basel.int/theconvention/overview/tabid/1271/default.aspx

EU Ship Recycling Regulation (EU SRR) - https://environment.ec.europa.eu/topics/waste-and-recycling/ships_en

Hazardous Materials (HAZMAT) - Substances in quantities or forms that may pose a reasonable risk to health, property, or the environment. HAZMATs include such substances as toxic chemicals, fuels, nuclear waste products, and biological, chemical, and radiological agents. HAZMATs may be released as liquids, solids, gases, or a combination or form of all three, including dust, fumes, gas, vapor, mist, and smoke (Source: Ocean Service).

Hazardous Waste - A waste with properties that make it dangerous or capable of having a harmful effect on human health or the environment. Hazardous waste is generated from many sources, ranging from industrial manufacturing process wastes to batteries and may come in many forms, including liquids, solids gases, and sludges (Source: EPA government).

Heavy metals - Heavy metals are generally defined as metals with relatively high densities, atomic weights. Examples of heavy metals include mercury (Hg), cadmium (Cd), arsenic (As), chromium (Cr), thallium (Tl), and lead (Pb) (Source: Lenntech).

Hong Kong Convention (HKC) - https://www.imo.org/en/about/Conventions/pages/the-hong-kong-international-convention-for-the-safe-and-environmentally-sound-recycling-of-ships.aspx

Oil residues - Means the residual waste oil products generated during the normal operation of a ship such as those resulting from the purification of fuel or lubricating oil for main or auxiliary machinery, separated waste oil from oil filtering equipment, waste oil collected in drip trays, and waste hydraulic and lubricating oils (Source: IADC)

Persistent organic pollutants - Organic substances that persist in the environment, accumulate in living organisms and pose a risk to our health and the environment (Source: ECHA Europa).

Recycling - The action or process of converting waste into reusable material. (Source: Oxford Dictionary)

Shipbreaking Yard - Also known as ship graveyards or ship demolition yards, are facilities where decommissioned or obsolete ships are dismantled and their parts recycled (Source: English docs)

Toxic Waste - Chemical waste material capable of causing death or injury to life. Waste is considered toxic if it is poisonous, radioactive, explosive, carcinogenic (causing cancer), mutagenic (causing damage to chromosomes), teratogenic (causing birth defects), or bio accumulative (that is, increasing in concentration at the higher ends of food chains) (Source: Britannica).

Wastewater treatment - The removal of impurities from wastewater, or sewage, before it reaches aquifers or natural bodies of water such as rivers, lakes, estuaries, and oceans (Source: Britannica)

Sources

Environmental Pollution in Shipbreaking

Shipbreaking BD,

Shipbreaking in Bangladesh: The Labor of Living with Toxic Development

Anthropology News, 2020

Off the Beach

Off the Beach,

Annual Lists of Shipbreaking

Shipbreaking Platform,

The Law and Shipbreaking

Shipbreaking Platform,

https://shipbreakingplatform.org/issues-of-interest/the-law/

Death, Injury, and Disease in Shipbreaking

Equal Times, 2020

https://www.equaltimes.org/death-injury-and-disease-the?lang=fr

Trading Lives for Profit: How the Shipping Industry Circumvents Regulations on Scrap Toxic Ships

Human Rights Watch, 2023

Asbestos-Related Disease in Bangladeshi Shipbreakers

Courtice, 2011https://www.shipbreakingplatform.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/Courtice-2011-Asbestos-related-disease-in-Bangladeshi-shipbreakers.pdf

New Rules May Not Change Dirty and Deadly Ship Recycling Business

France24, 2025https://www.france24.com/en/live-news/20250618-new-rules-may-not-change-dirty-and-deadly-ship-recycling-business

Environmental Costs of Shipbreaking

Shipbreaking Platform

https://shipbreakingplatform.org/our-work/the-problem/environmental-costs/

Shipbreaking and Hazardous Waste Regulations

U.S. Government Publishing Office

https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/GOVPUB-L35-PURL-gpo14904/pdf/GOVPUB-L35-PURL-gpo14904.pdf

Flags of Convenience in Shipping

International Transport Workers’ Federation

https://www.itfglobal.org/en/sector/seafarers/flags-convenience

The Hong Kong International Convention for Safe and Environmentally Sound Recycling of Ships

International Maritime Organization

EU Ship Recycling Regulation

Shipbreaking Platform

https://shipbreakingplatform.org/issues-of-interest/the-law/eu-srr/

The Human Cost of Shipbreaking

Shipbreaking Platform

https://shipbreakingplatform.org/our-work/the-problem/human-costs/

Boom in Ship Demolitions by 2032

Port News, 2023

https://www.portnews.it/en/boom-di-demolizioni-entro-il-2032/

Oil Residue (Sludge) in Shipbreaking

IADC Lexicon

Heavy Metals in Industrial Processes

Lenntech

https://www.lenntech.com/processes/heavy/heavy-metals/heavy-metals.htm

Shipbreaking Yards Overview

English Docs

Hazardous Materials (HAZMAT) Facts

NOAA Ocean Service

Basics of Hazardous Waste

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency

Understanding Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs)

European Chemicals Agency

Toxic Waste

Britannica

Wastewater Treatment

Britannica

Steel Demand and Shipbreaking in Bangladesh

Plymouth University, 2024

https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2395&context=secam-research

Chowdhury, Ahmed & Islam, Saiful & Era, Samiha. (2024). Bangladesh Ship Breaking Industry and Livelihood Assessment of Out-Migrant Workers: A Study of Southern - Northern Region in Bangladesh. International Journal of Social Science and Religion (IJSSR). 375-396. 10.53639/ijssr.v5i3.256.